The money multiplier measures how an initial deposit can lead to a greater final increase in the total money supply through the banking system's lending processes. This concept plays a crucial role in understanding how central bank policies influence economic growth and inflation. Explore the rest of the article to learn how the money multiplier impacts Your financial environment and broader economic stability.

Table of Comparison

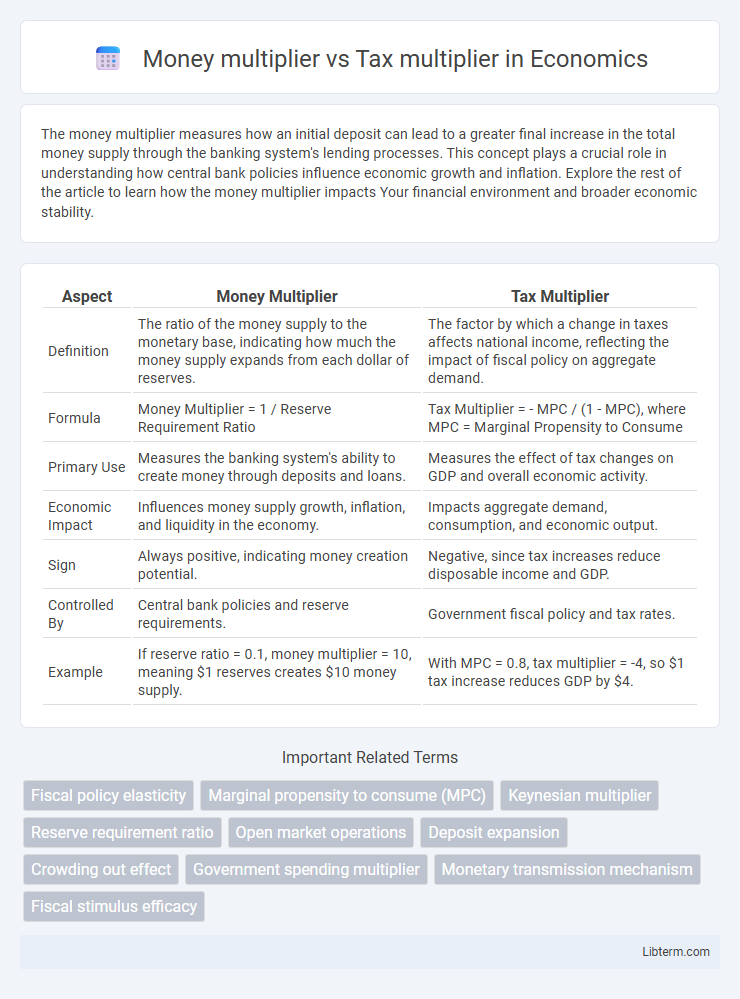

| Aspect | Money Multiplier | Tax Multiplier |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The ratio of the money supply to the monetary base, indicating how much the money supply expands from each dollar of reserves. | The factor by which a change in taxes affects national income, reflecting the impact of fiscal policy on aggregate demand. |

| Formula | Money Multiplier = 1 / Reserve Requirement Ratio | Tax Multiplier = - MPC / (1 - MPC), where MPC = Marginal Propensity to Consume |

| Primary Use | Measures the banking system's ability to create money through deposits and loans. | Measures the effect of tax changes on GDP and overall economic activity. |

| Economic Impact | Influences money supply growth, inflation, and liquidity in the economy. | Impacts aggregate demand, consumption, and economic output. |

| Sign | Always positive, indicating money creation potential. | Negative, since tax increases reduce disposable income and GDP. |

| Controlled By | Central bank policies and reserve requirements. | Government fiscal policy and tax rates. |

| Example | If reserve ratio = 0.1, money multiplier = 10, meaning $1 reserves creates $10 money supply. | With MPC = 0.8, tax multiplier = -4, so $1 tax increase reduces GDP by $4. |

Introduction to Fiscal Multipliers

Fiscal multipliers measure the impact of government spending or taxation changes on overall economic output. The money multiplier quantifies how an initial injection of money increases total money supply through banking activities, while the tax multiplier assesses how changes in taxes affect aggregate demand and GDP. Understanding these multipliers is crucial for policymakers aiming to stabilize or stimulate the economy through fiscal measures.

Defining the Money Multiplier

The money multiplier measures the maximum amount of money the banking system can generate with each unit of reserves, reflecting the relationship between reserves and total money supply. It is calculated as the reciprocal of the reserve ratio, indicating how central bank reserves translate into broader money creation through deposit multiplication. In contrast, the tax multiplier represents the change in aggregate demand caused by a change in taxes, highlighting fiscal policy impacts rather than the monetary supply process.

Understanding the Tax Multiplier

The tax multiplier measures the change in aggregate demand resulting from a change in taxes and is typically smaller in magnitude than the money multiplier, which reflects the impact of monetary base expansion on the overall money supply. Understanding the tax multiplier involves analyzing how variations in tax policy influence disposable income, consumption, and consequently aggregate demand. Empirical studies show that a 1% increase in taxes can reduce GDP by less than 1%, highlighting the tax multiplier's relatively moderate effect compared to monetary multipliers.

Mechanisms of the Money Multiplier

The money multiplier mechanism operates through the banking system's capacity to create money by lending a portion of deposits while keeping reserves, thus expanding the money supply beyond the initial injection. This process hinges on the reserve requirement ratio, where a lower ratio increases the multiplier effect by enabling banks to lend more. In contrast, the tax multiplier affects aggregate demand by altering disposable income and consumption, impacting economic activity indirectly rather than through direct money creation.

Mechanisms of the Tax Multiplier

The tax multiplier measures the change in aggregate demand caused by a change in taxes, operating through households' disposable income and consumption patterns. When taxes decrease, disposable income rises, leading to increased consumption and thus higher aggregate demand, with the magnitude influenced by the marginal propensity to consume (MPC). Unlike the money multiplier, which expands the money supply through banking reserves and lending, the tax multiplier directly alters fiscal policy's impact on economic output via changes in taxation and consumer spending behavior.

Key Differences Between Money and Tax Multipliers

The money multiplier measures the maximum amount of commercial bank money created through the banking system for a given reserve ratio, influencing the overall money supply and liquidity. In contrast, the tax multiplier quantifies the impact of a change in taxation on aggregate demand, directly affecting consumer spending and economic output. Key differences include the money multiplier's role in money creation via fractional reserve banking versus the tax multiplier's function in fiscal policy to modify disposable income and aggregate demand.

Factors Influencing Multiplier Effects

The money multiplier is influenced primarily by factors such as the reserve ratio set by central banks, currency holdings by the public, and excess reserves kept by banks, which affect the overall credit creation in an economy. In contrast, the tax multiplier depends on the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), tax rates, and the structure of the tax system, influencing how changes in taxes impact aggregate demand. Both multipliers demonstrate that monetary policy effectiveness hinges on banking behavior, while fiscal policy responsiveness is shaped by consumer spending patterns and taxation mechanisms.

Real-World Examples: Money vs. Tax Multipliers

The money multiplier reflects how an initial deposit expands total money supply through banking lending, with a typical value around 2 to 5 in stable economies like the United States. Tax multipliers measure changes in GDP resulting from changes in taxation, often estimated between -0.5 and -1.5, as observed during tax cuts in the 2008 financial crisis and the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, where the real economy's response showed limited but notable stimulus effects. Real-world applications reveal money multipliers directly influence liquidity and credit availability, whereas tax multipliers primarily affect aggregate demand and consumer spending patterns.

Policy Implications and Economic Impact

The money multiplier influences monetary policy by determining how changes in the central bank's reserve requirements affect the total money supply, impacting inflation and economic growth. The tax multiplier shapes fiscal policy effectiveness by measuring how changes in taxation influence aggregate demand and national income, crucial for managing economic recessions or overheating. Policymakers must balance these multipliers to optimize economic stability, controlling inflation without stifling growth or employment.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right Multiplier Strategy

Selecting the appropriate multiplier strategy depends on the economic context and policy objectives; the money multiplier primarily influences the money supply and credit creation, while the tax multiplier directly affects aggregate demand through taxation changes. Policymakers aiming to stimulate short-term consumption may prefer the tax multiplier for its immediate impact on disposable income, whereas long-term financial stability goals align better with the money multiplier's role in regulating banking reserves and lending capacity. Effective economic management requires balancing these multipliers to optimize growth and control inflation.

Money multiplier Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com