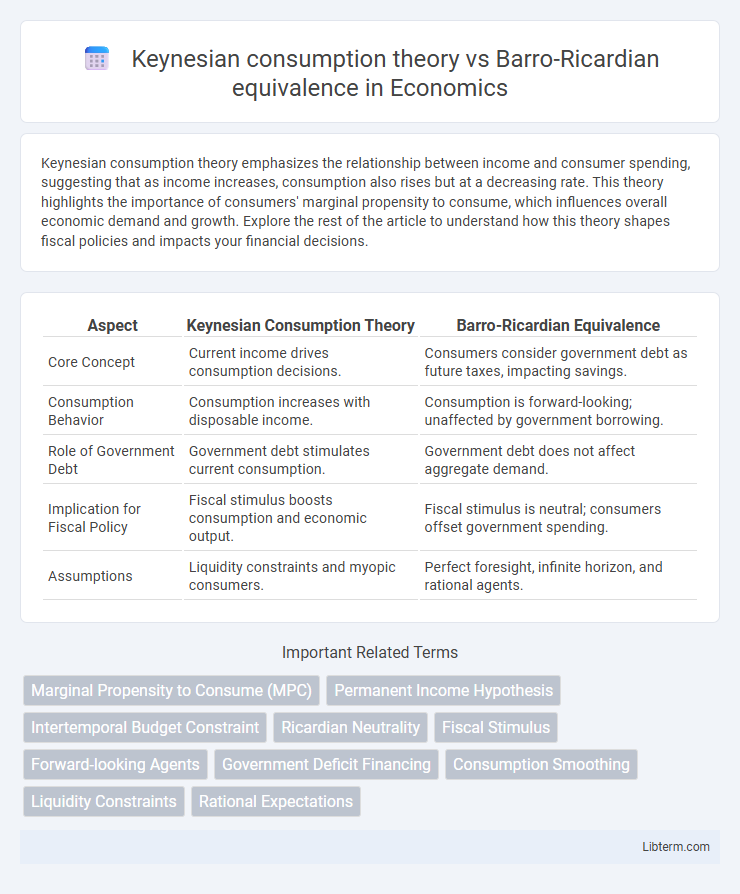

Keynesian consumption theory emphasizes the relationship between income and consumer spending, suggesting that as income increases, consumption also rises but at a decreasing rate. This theory highlights the importance of consumers' marginal propensity to consume, which influences overall economic demand and growth. Explore the rest of the article to understand how this theory shapes fiscal policies and impacts your financial decisions.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Keynesian Consumption Theory | Barro-Ricardian Equivalence |

|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | Current income drives consumption decisions. | Consumers consider government debt as future taxes, impacting savings. |

| Consumption Behavior | Consumption increases with disposable income. | Consumption is forward-looking; unaffected by government borrowing. |

| Role of Government Debt | Government debt stimulates current consumption. | Government debt does not affect aggregate demand. |

| Implication for Fiscal Policy | Fiscal stimulus boosts consumption and economic output. | Fiscal stimulus is neutral; consumers offset government spending. |

| Assumptions | Liquidity constraints and myopic consumers. | Perfect foresight, infinite horizon, and rational agents. |

Introduction to Consumption Theories

Keynesian consumption theory emphasizes current income as the primary determinant of consumer spending, positing that individuals tend to consume a fixed proportion of their disposable income. In contrast, the Barro-Ricardian equivalence hypothesis argues that consumers anticipate future taxes associated with government debt, leading them to save rather than increase consumption when the government runs deficits. These foundational consumption theories shape differing perspectives on fiscal policy effectiveness, with Keynesians supporting demand-driven stimuli and Barro-Ricardian proponents highlighting the neutral impact of deficit-financed spending on aggregate consumption.

Overview of Keynesian Consumption Theory

Keynesian Consumption Theory posits that current income directly influences consumer spending, with households primarily driven by their present disposable income rather than anticipated future earnings. The theory emphasizes the marginal propensity to consume, suggesting individuals spend a consistent fraction of any additional income, thereby stimulating aggregate demand. Contrasting this, Barro-Ricardian equivalence argues that consumers internalize government budget constraints, saving current income to offset future tax liabilities, thus neutralizing fiscal policy effects on consumption.

Fundamentals of Barro-Ricardian Equivalence

Barro-Ricardian equivalence asserts that consumers anticipate future taxes resulting from government debt and therefore increase their savings to offset anticipated tax liabilities, nullifying the stimulative effects of fiscal deficits. This contrasts with Keynesian consumption theory, which posits that current income drives consumption, making fiscal policy effective in managing aggregate demand. The fundamental assumption of Barro-Ricardian equivalence rests on rational, forward-looking agents, perfect capital markets, and intergenerational altruism ensuring that government borrowing does not affect overall consumption levels.

Core Assumptions of Each Theory

Keynesian consumption theory assumes that consumers base their spending primarily on current income, emphasizing liquidity constraints and a propensity to consume out of present earnings. Barro-Ricardian equivalence posits that consumers are forward-looking and perceive government debt as future taxes, leading them to save accordingly to offset public borrowing. The core assumption distinguishing the two is that Keynesians view fiscal deficits as stimulative due to immediate consumption increases, while Barro-Ricardian theorists argue these deficits have no effect on aggregate demand since rational agents anticipate tax liabilities.

Marginal Propensity to Consume: Keynes vs. Ricardian

Keynesian consumption theory posits a high Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC), suggesting individuals increase their consumption substantially when disposable income rises, driving aggregate demand and economic fluctuations. In contrast, Barro-Ricardian equivalence argues the MPC is effectively zero because rational agents anticipate future tax liabilities from government borrowing, leading them to save rather than spend increased government transfers. Empirical studies often find MPC values between these extremes, reflecting a complex interplay of behavioral responses and expectations in consumption patterns.

Role of Government Policy in Both Theories

Keynesian consumption theory emphasizes that government fiscal policies, such as increased public spending and tax cuts, directly stimulate aggregate demand by boosting consumer spending in the short term. In contrast, Barro-Ricardian equivalence argues that government borrowing does not affect overall consumption because individuals anticipate future tax liabilities and therefore save any government transfers, offsetting fiscal stimulus. The distinction hinges on the effectiveness of government policy in altering consumption patterns: Keynesian theory supports active intervention to manage economic cycles, while Barro-Ricardian equivalence suggests that fiscal policy is neutral in its impact on aggregate demand.

Short-Run Versus Long-Run Consumption Effects

Keynesian consumption theory emphasizes that current disposable income drives consumer spending, leading to a strong short-run consumption response to fiscal policy changes. In contrast, the Barro-Ricardian equivalence hypothesis argues that consumers anticipate future taxes associated with government debt, resulting in neutral long-run consumption effects despite short-term fiscal stimulus. Empirical evidence often shows Keynesian effects dominate in the short run, while Barro-Ricardian neutrality may hold under certain assumptions over the long run.

Empirical Evidence and Real-World Applications

Empirical evidence for Keynesian consumption theory highlights the positive correlation between current income and consumer spending, supporting the theory's prediction that fiscal stimulus boosts aggregate demand. In contrast, Barro-Ricardian equivalence suggests that consumers anticipate future taxes from government borrowing and thus do not change their consumption significantly, but empirical studies often find limited support for this fully offsetting behavior. Real-world applications show that Keynesian models guide active fiscal policy interventions to stabilize economies during recessions, while the Barro-Ricardian perspective influences debates on the long-term effects of government debt and tax policies.

Criticisms and Limitations of Both Theories

Keynesian consumption theory faces criticism for its assumption that consumers base spending solely on current income, overlooking future expectations and intertemporal choices. Barro-Ricardian equivalence is limited by its unrealistic presumption of perfect rationality and full access to capital markets, which many households do not possess. Both theories struggle with empirical inconsistencies, as Keynesian models underpredict saving behavior while Ricardian equivalence often fails in real-world scenarios where liquidity constraints and uncertainty prevail.

Implications for Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth

Keynesian consumption theory implies that fiscal policy, especially government spending and tax cuts, can stimulate aggregate demand and promote short-term economic growth by increasing consumer spending. In contrast, the Barro-Ricardian equivalence posits that consumers anticipate future taxes associated with government debt, leading them to save rather than spend fiscal stimulus, thereby neutralizing its impact on aggregate demand and economic growth. These differing perspectives affect how policymakers design fiscal interventions, with Keynesianism supporting active fiscal measures to boost growth and Barro-Ricardian equivalence suggesting limited effectiveness of such policies due to forward-looking consumer behavior.

Keynesian consumption theory Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com