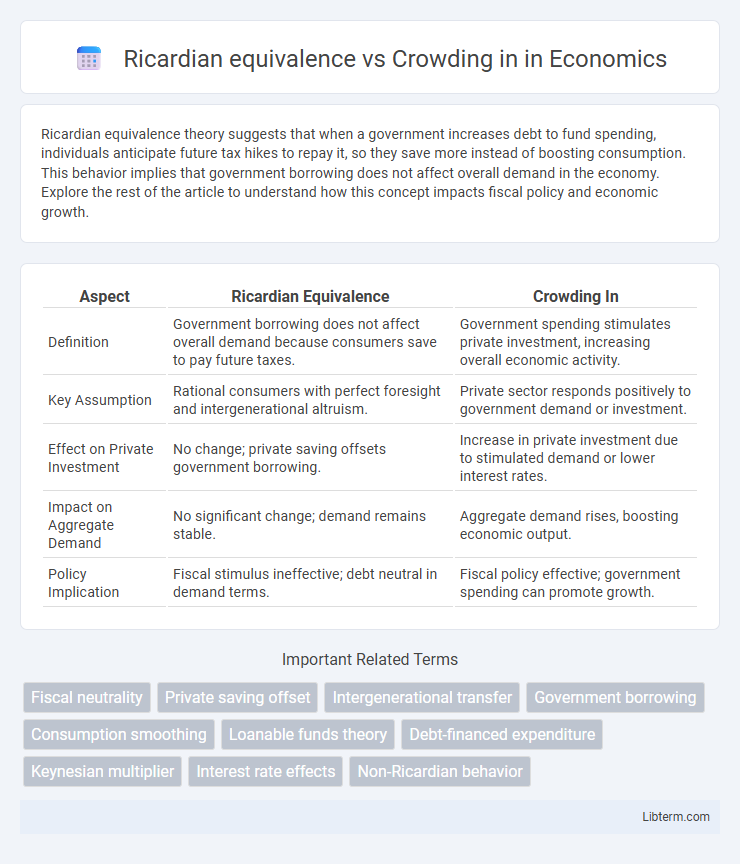

Ricardian equivalence theory suggests that when a government increases debt to fund spending, individuals anticipate future tax hikes to repay it, so they save more instead of boosting consumption. This behavior implies that government borrowing does not affect overall demand in the economy. Explore the rest of the article to understand how this concept impacts fiscal policy and economic growth.

Table of Comparison

| Aspect | Ricardian Equivalence | Crowding In |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Government borrowing does not affect overall demand because consumers save to pay future taxes. | Government spending stimulates private investment, increasing overall economic activity. |

| Key Assumption | Rational consumers with perfect foresight and intergenerational altruism. | Private sector responds positively to government demand or investment. |

| Effect on Private Investment | No change; private saving offsets government borrowing. | Increase in private investment due to stimulated demand or lower interest rates. |

| Impact on Aggregate Demand | No significant change; demand remains stable. | Aggregate demand rises, boosting economic output. |

| Policy Implication | Fiscal stimulus ineffective; debt neutral in demand terms. | Fiscal policy effective; government spending can promote growth. |

Introduction to Ricardian Equivalence and Crowding In

Ricardian equivalence posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes and increase savings accordingly, neutralizing fiscal stimulus. Crowding in occurs when government spending boosts private sector investment and consumption by improving economic conditions or confidence. Understanding these concepts highlights contrasting effects of fiscal policy on aggregate demand and private investment dynamics.

Theoretical Foundations of Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian equivalence theory posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future tax liabilities and thus increase savings to offset government debt. This contrasts with the crowding-in effect, where government spending stimulates private investment by increasing aggregate demand and improving business confidence. The theoretical foundation of Ricardian equivalence relies on assumptions of perfect capital markets, infinite planning horizons, and rational, forward-looking consumers who internalize government budget constraints.

Understanding the Concept of Crowding In

Crowding in refers to the phenomenon where increased government spending stimulates private sector investment by improving economic conditions or reducing uncertainties. Unlike Ricardian equivalence, which posits that individuals anticipate future taxes and thus offset government borrowing, crowding in suggests a positive fiscal multiplier effect through enhanced business confidence and resource availability. Empirical evidence often shows that government expenditure in infrastructure or innovation can boost private investment, highlighting the importance of fiscal policy design.

Key Assumptions Underlying Ricardian Equivalence

Ricardian equivalence hinges on assumptions such as rational, forward-looking agents who perfectly anticipate future taxes and have infinite lifespans or altruistic preferences to transfer wealth intergenerationally. It assumes capital markets are perfect, allowing individuals to borrow and save freely to smooth consumption despite government borrowing changes. These assumptions contrast with crowding-in effects, where government spending stimulates private investment, often occurring when credit markets are imperfect or agents are liquidity constrained.

Mechanisms and Drivers Behind Crowding In

Crowding in occurs when increased government spending stimulates private sector investment by enhancing economic confidence or providing complementary infrastructure, thus expanding overall demand. Mechanisms driving crowding in include reductions in interest rates due to improved fiscal stability and increased business expectations about future growth and profitability. Contrary to Ricardian equivalence, which predicts unchanged private spending as individuals anticipate future taxes, crowding in emphasizes positive feedback loops where government expenditure catalyzes greater private investment activity.

Empirical Evidence on Ricardian Equivalence

Empirical evidence on Ricardian equivalence reveals mixed results, with some studies indicating that consumers partially offset government borrowing by increasing savings, while others show limited or no offsetting behavior. Research often highlights factors such as liquidity constraints, finite planning horizons, and imperfect capital markets that weaken the equivalence proposition. Crowding in effects, where increased public investment stimulates private investment, further challenge the strict assumptions of Ricardian equivalence by demonstrating positive fiscal multipliers in various economies.

Factors Promoting Crowding In Effects

Crowding-in effects occur when increased government spending stimulates private sector investment by boosting overall economic demand and improving business confidence. Factors promoting crowding-in include low interest rates, which reduce the cost of borrowing, and underutilized resources, allowing private investment to expand without driving up costs. Furthermore, Ricardian equivalence may not hold if consumers face credit constraints or have finite planning horizons, enabling fiscal policy to effectively encourage private sector activity.

Fiscal Policy Implications: Ricardian vs. Crowding In

Ricardian equivalence suggests that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future taxes and increase their savings accordingly, neutralizing fiscal stimulus effects. In contrast, crowding in occurs when increased government spending stimulates private investment, enhancing overall economic activity through higher demand or improved business confidence. Fiscal policy under Ricardian equivalence requires careful consideration of private savings behavior, while crowding in implies that strategic government expenditure can effectively boost growth and private sector investment.

Real-World Case Studies and Comparative Analysis

Ricardian equivalence posits that government borrowing does not affect overall demand because individuals anticipate future tax liabilities and increase savings accordingly, a principle demonstrated in some European countries during fiscal expansions. Crowding in, observed in developing economies like India, occurs when government investment stimulates private sector confidence and boosts private investment, counteracting potential displacement effects. Comparative analysis reveals that crowding in tends to dominate in emerging markets with underutilized resources, while Ricardian equivalence holds more in mature economies with forward-looking consumers.

Conclusion: Policy Relevance and Future Research Directions

Ricardian equivalence challenges the effectiveness of fiscal policy by suggesting that government borrowing does not influence overall demand, as consumers anticipate future taxes and adjust their savings accordingly. Crowding in theory argues that government spending can stimulate private investment by improving economic conditions or reducing interest rates. Future research should explore the conditions under which each phenomenon dominates, focusing on heterogeneous agent models and the role of financial markets to inform more precise fiscal policy design.

Ricardian equivalence Infographic

libterm.com

libterm.com